Deferring criticism while reading

I recently finished a book by Dorothea Brande called Becoming a writer. Rather than describe plot formulas or detail how to write character outlines, she describes how to use one’s character and develop one’s habits so as to become a writer. In the process she also has some interesting points to make about reading and criticism.

Withholding criticism

One of the main strands of advice running through Brande’s book is that a would-be writer should learn to reserve criticism for the right time. In order to tap into one’s talents, she advises, one must write from the unconscious, put the resulting work away and only later return to it.

Practically, her instructions on achieving this include writing first thing in the morning before one reads a single other thing (so as to avoid influence) and making appointments for oneself to write at particular times.

Reading

Similar advice applies to reading. If one is serious about becoming a writer, one wants to gain as much as possible from the materials one reads. I know I do.

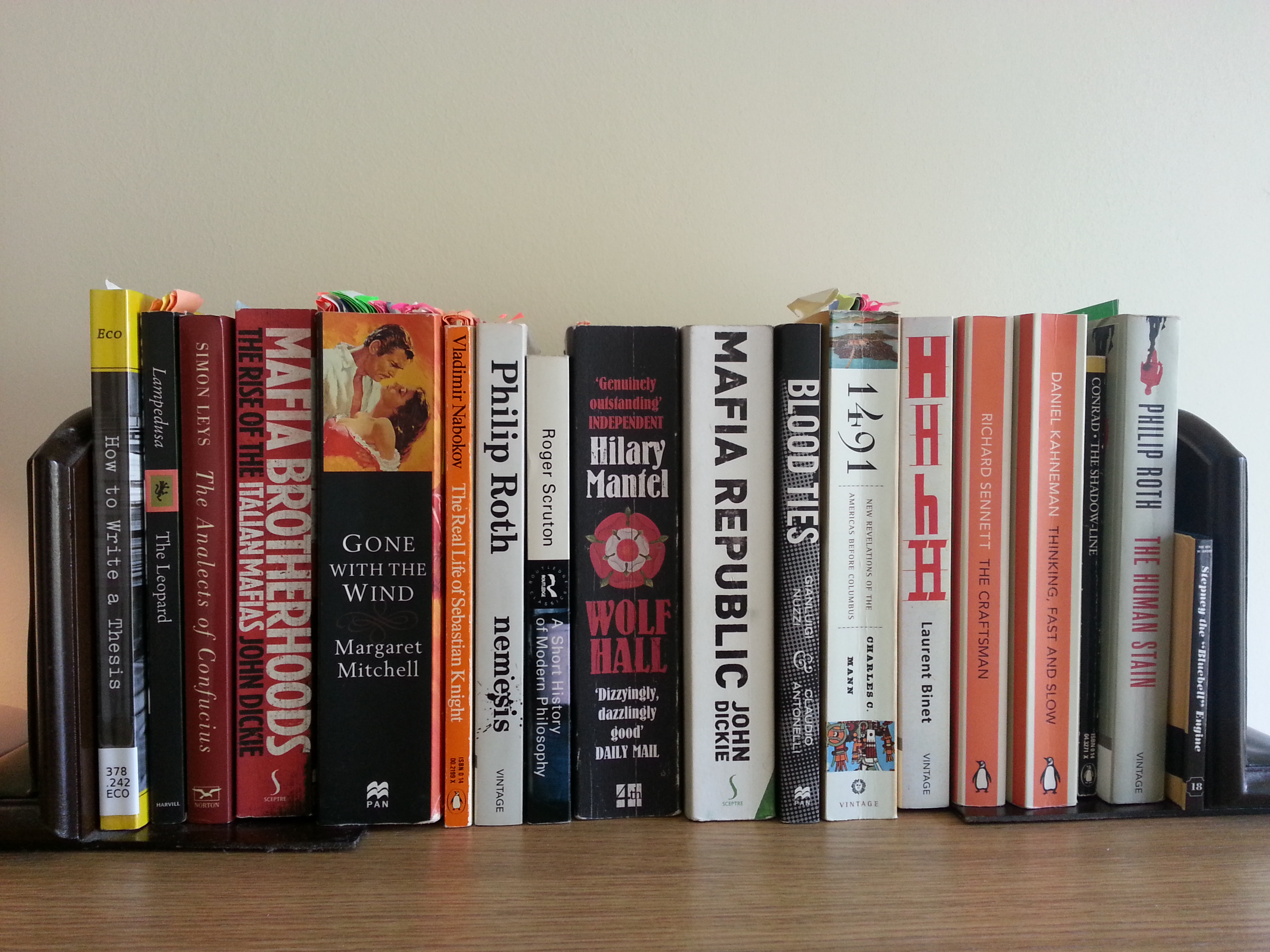

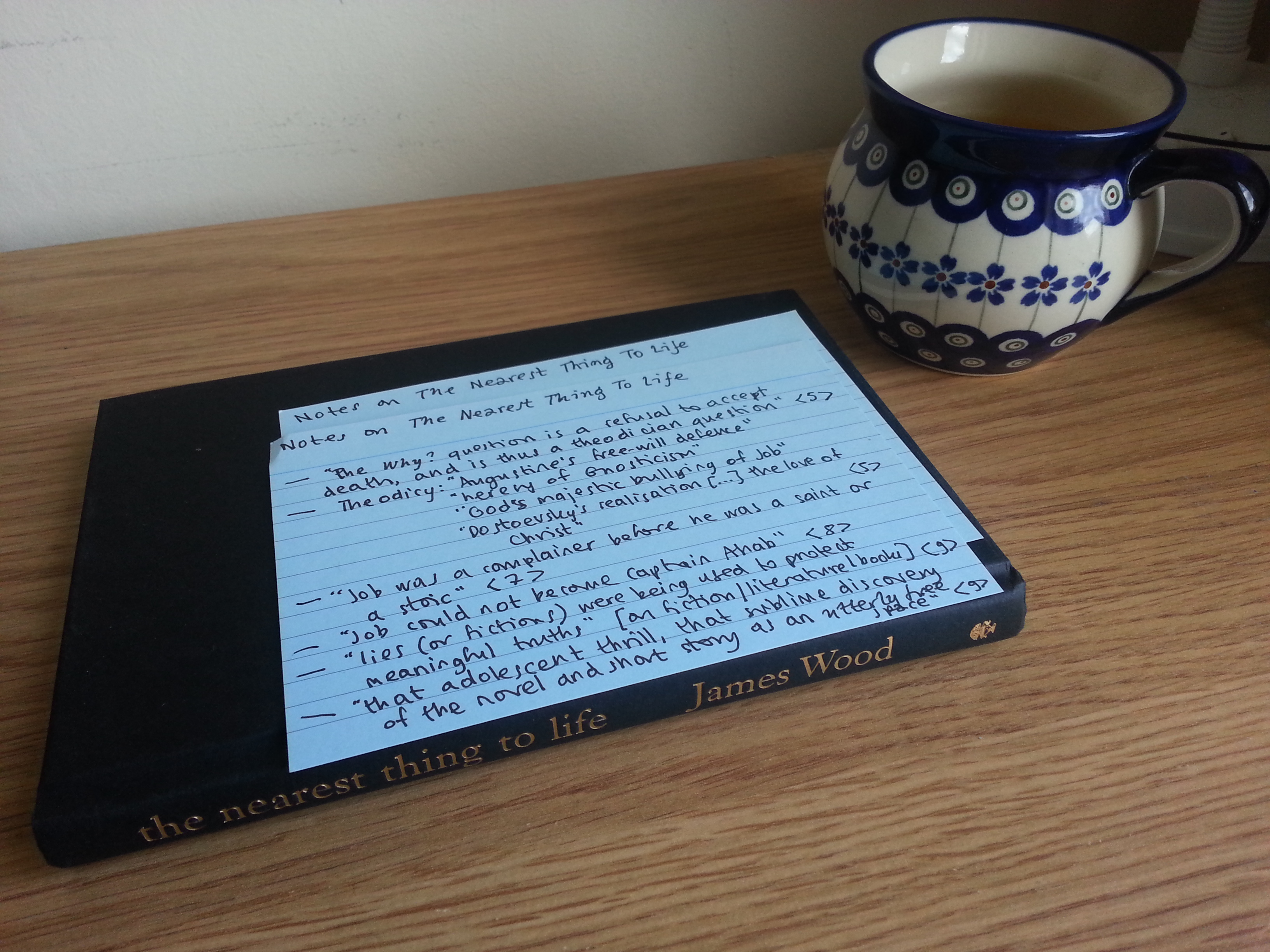

For me, in the last year or so, this has moved from leaving scribbled on sticky notes in the relevant pages of a book to keeping an index card slotted into whatever book I’m reading, ready to scribble notes on at any point I feel like it.

I intend to continue doing this for now but Brande’s advice is interesting. As with writing, she advises having a first uncritical read-through, where one reads the book in pause-less sessions.

On completing a book, she then recommends making a “summary judgement”1:

Make a short written synopsis of what you have just read. Now pass a kind of summary judgement on it: you liked it, or didn’t like it. You believed it, or were left incredulous. You like part of it, disliked the rest. (You may, if you like later pass a moral judgement on it, too, but now confine your decisions to what you believe were the author’s intentions, as far as you are able to discern them.)

Go on to enlarge these flat statements. If you liked it, why did you? […] If part of it seemed good to you and the rest weak, see whether you are able to tell when the author lost your assent. [pp100-101]

Brande is largely dealing with the writing and reading of fiction in her book so other questions follow that are more specific to that type of book.

Were the characters drawn with uniform skill, badly drawn, or inconsistent only occasionally? Do you know why you felt this?

Do any of the scenes stand out in your mind? Because they were well done, or because an opportunity was so stupidly missed? Remember any passage which arrested your attention for any reason. Is the dialogue natural, or, if stylised, is the formality purposeful or a sign of the author’s limitations? [p101]

I think these sorts of questions could to some extent be applied to non-fiction too though (particularly, if taking into account the claim of Aleksander Hemon and others that the divide between fiction and non-fiction is a specifically English language phenomenon). And Brande advises us not to be discouraged if the answers to these questions seem vague; she reassures us that we “are going to read the book again”.

Ultimately she comes back to questions that should be relevant to any writer looking to learn about writing through the process of reading.

[…] How does the author you have just read handle situations which would be difficult for you? [p101]

First impressions

Brande’s suggestion that we re-read a book to analyse it, rather than trying to do it on the first pass, puts me in mind of Vladimir Nabokov’s paradoxical assertion that one never reads a book; one re-reads it.

This is from Nabokov’s Lectures on Literature2:

When we read a book for the first time the very process of laboriously moving our eyes from left to right, line after line, page after page, this complicated physical work upon the book, the very process of learning in terms of space and time what the book is about, this stands between us and artistic appreciation. When we look at a painting we do not have to move our eyes in a special way even if, as in a book, the picture contains elements of depth and development. The element of time does not really enter in a first contact with a painting. In reading a book, we must have time to acquaint ourselves with it. We have no physical organ (as we have the eye in regard to painting) that takes in the whole picture and then can enjoy its details. But at a second, or third, or fourth reading we do, in a sense, behave towards a book as we do towards a painting.

Although there’s a simpler argument from Nabokov which I think supports Brande’s suggestion that we ought read first of all, as we ought to write first of all, without seeking to analyse:

It is no use reading a book at all if you do not read it with your back.

Ironically, the book I have myself re-reading the most recently is Brande’s. I find myself revisiting sections and although I haven’t followed her advice to letter, I feel her book has steered me in the right direction on reading.

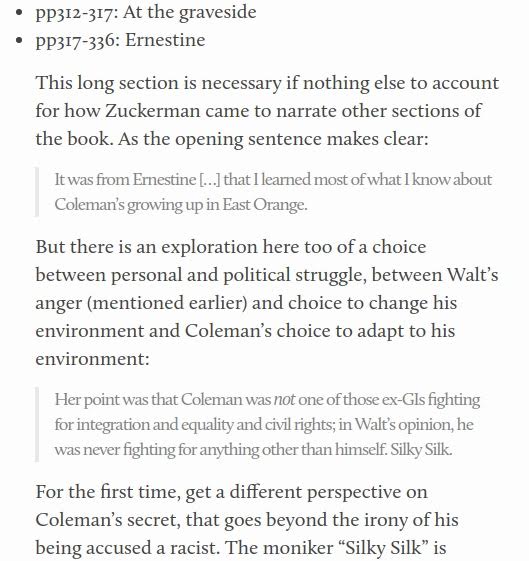

Recently, while reading Roth’s The Human Stain I have found myself before picking up the book to dive into the story again, typing up a summary what has happened in the last reading session and sometimes even picking out quotations I like, passages I thought were well-executed, examples of things that worked – and I imagine if I wasn’t reading a master like Roth, I’d be noting passages that didn’t work so well too.

So I’m not following Brande’s advice exactly yet. But my note-taking creates a map of the book and my instinctive reactions to it as I read it for the first time, which I’m hoping will prove useful when I come to re-read and dissect it later.

Next

Reading Brande has already put me into a different mindset around reading and the right time to record my thoughts. I’m going to continue to experiment and I’ll note any discoveries here. But I also want to link this back to the thoughts I was having late last year around ways of recording facts and information. To do that, I will need to type up the notes I already have.

–