Creating through failing

In this post, I use the continuation of my labyrinth experiment as a way of practically looking at “behaviour-driven development” (BDD), a method for developing code by testing first, failing, and then creating until one passes the tests.

Re-cap

In order to explore the idea of behaviour-driven development, I will use the seemingly simple labyrinth problem I’ve been thinking about over the last two weeks.

In the last couple of posts, I’ve walked through the possibility of coding a labyrinth or maze creator and creating a function that could test the difficulty of a labyrinth. This post, I continue that process creating a prototype of my “walkthrough” function and testing it with tests I know it won’t pass. I think bring the function up to the bar by developing it until it does pass.

What is BDD?

I don’t want to go into lots of detail about the theory and history of BDD for this post. It is interesting but there’s a fairly comprehensive Wikipedia page on BDD already. I’m more interested in showing how you can use it in practice.

The main principles to be aware of is that one starts by defining the expected behaviour of the code one is writing. One does that by writing “unit tests”, little isolated tests that pass or fail based on the results expected. The tests fail at first; you create your code through failure.

Passing the first test

Last post I wrote the following test using Mocha and the library “should.js”:

var should = require("should")

var dictionary = {

"a": "0000",

"b": "1111",

"p": "1010",

"q": "0101",

"n": "1000",

"e": "0100",

"s": "0010",

"w": "0001",

"r": "1001",

"t": "1100",

"j": "0110",

"l": "0011",

"u": "0111",

"c": "1011",

"n": "1101",

"d": "1110"

}

describe("Walkthrough function", () => {

var walkthrough = require("./../walkthrough.js").walkthrough

it("should ", function () {

walkthrough("a", [1, 1], false, dictionary).should.eql({

"coverage": 1,

"completion": true,

"paths": 1,

"distance": 1

})

})

})

This is a test. It takes a function called walkthrough and it says that with certain input it should return certain values as its output.

I can write a function called walkthrough that simply returns an empty object, whatever the inputs:

var walkthrough = function (maze, entrance, exit, dictionary) {

return {}

}

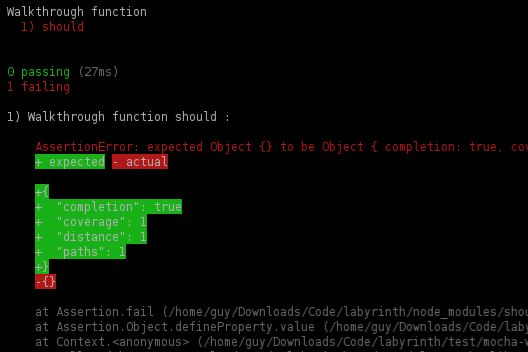

When I run my test however, it will fail. The result returned by function is not the one expected.

The test should force me to develop the function until it passes.

There’s a really easy way to do this. I can just code my function so that it returns the code that the test expects.

var walkthrough = function (maze, entrance, exit, dictionary) {

return {

"coverage": 1,

"completion": true,

"paths": 1,

"distance": 1

}

}

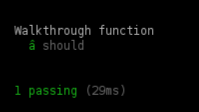

The test will now pass.

But if I give it a different set of inputs that require a different set of outputs it’s clear that the one test I’ve written is enough to define what I expect.

I need to write more tests and then I should develop my function accordingly.

Creating more tests

Although I’ve defined a dictionary of different tiles based on different possible wall configurations in my labyrinth (outlined in my post on encoding a labyrinth), I want to first define some basic tests around different numbers of tiles. So I will keep to the a tile for now.

For example, if I have a 2 x 2 sized maze with these tiles then I need to write a test that shows what to expect in that situation.

it("should be able to process mazes bigger than one tile", function () {

walkthrough("aaaa", [1, 1], false, dictionary).should.eql({

"coverage": 4,

"completion": true,

"paths": 2,

"distance": 4

})

})

Because I’m using the open a tile with no walls I expect the coverage property to reflect the number of tiles described in the input – there are no barriers to reaching every tile. Likewise, the distance to cover the entire maze is 4. There are two ways around the maze – one direction or the other.

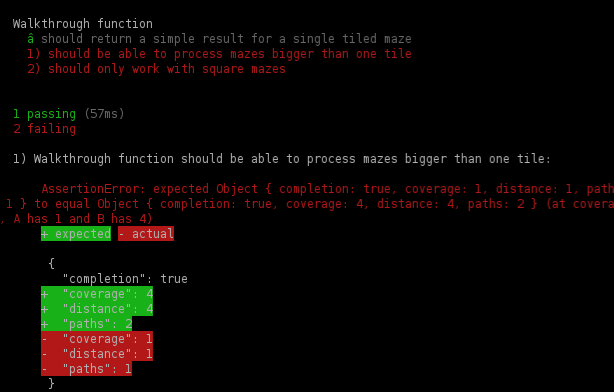

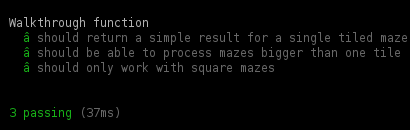

The description given after it – in this case should be able to process mazes bigger than one tile – gives me a clue when the test is run as to what has passed or failed.

I could keep expanding the maze – to 3 x 3, to 4 x 4, testing with inputs of 9 and 16 character mazes respectively.

But what happens if I create a maze string that does not equate to a square. In such a case I want the function to throw some kind of error or not return the usual properties.

it("should only work with square mazes", function () {

walkthrough("aaa", [1, 1], false, dictionary).should.have.property("error")

})

In the example given, a string with three characters in it is expected to throw an error as we only want our function to accept square mazes.

Using just these two additional tests, we can define a lot about our function without even venturing into more complex tile arrangements.

At the moment, both tests fail so we need to develop the walkthrough function further until they pass.

Fleshing out the function

Of our two tests, let’s deal with the last one first. To pass the test I have written, the function must throw an error if the number is not a square of some other integer.

This can be done fairly easily by inserting a few lines of code rather than changing what’s already there, so that we have this.

var walkthrough = function (maze, entrance, exit, dictionary) {

var mazeIsSquare = maze.length > 0 && Math.sqrt(maze.length) % 1 === 0

if (!mazeIsSquare) return { error: true }

return {

"coverage": 1,

"completion": true,

"paths": 1,

"distance": 1

}

}

Now before returning anything the function checks to see if the maze is a square or not by checking the length of the maze string is positive and has an integer square root.

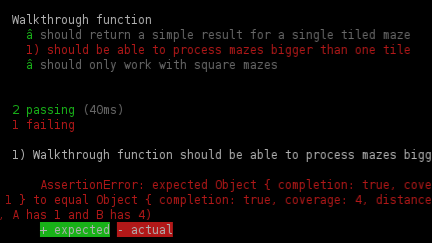

This seems very simple but it passes the test as specified.

To pass the remaining test, there will need to be changes to the existing lines of code in our function. This is because we need specific results based on the input. That is okay though; the whole point of building a suite of tests is not just finding edge cases and articulating what a function is – it’s also a good way to see if changes to the code that accommodate some new function or behaviour unintentionally break old functions or change existing behaviour.

var walkthrough = function (maze, entrance, exit, dictionary) {

var mazeIsSquare = maze.length > 0 && Math.sqrt(maze.length) % 1 === 0

if (!mazeIsSquare) return { error: true }

return {

"coverage": maze.length,

"completion": true,

"paths": Math.sqrt(maze.length),

"distance": maze.length

}

}

This causes success. Fortunately the changes I’ve made have not caused the first test to fail, else I would have to rethink the code and come up with another solution.

I already know that this version of the function will not pass future tests where the requirements are more exacting. But this is working code for now, and I can continue to cycle through testing and building quickly until I have something halfway viable. The idea is to continue building tests and then writing code that passes them.

Next: aspects of functions?

I have lots of different ideas to explore within this simple problem. One element that jumped out as I was writing this post, is the idea of separating type-checking and error-logging from a function. I could explore this through aspect-oriented programming, or through monads. In any case, I’ll continue to work away on this simple project as a way to demonstrate some different ideas about development.